Top Questions for 2021

- Doug Oosterhart, CFP®

- Jan 4, 2021

- 3 min read

2020 was a wild year. If an investor only looked at their account on January 1st, 2020, and then again on December 31st, 2020, they would've never known that the stock market experienced a massive downturn and then the biggest comeback to date.

Almost every emotion was experienced during 2020. I still remember calls with clients on March 20th (it was a Friday) talking people off the ledge when they asked, "shouldn't we just move to cash for a while? I don't think this is going to get any better."

It's definitely stressful for me, too. I don't like to see clients lose money on paper. I definitely wouldn't like to see clients lock in those losses by moving to cash at the bottom of a downturn.

That being said, there are some common questions arising after such a volatile year in the stock market. I'll do a little Q&A with them. Here are a few:

Should I invest at all-time highs? (This one occurs almost every year since, well, the market experiences a lot of all-time highs)

Here's an image that basically answers the question. Spoiler: just invest the money.

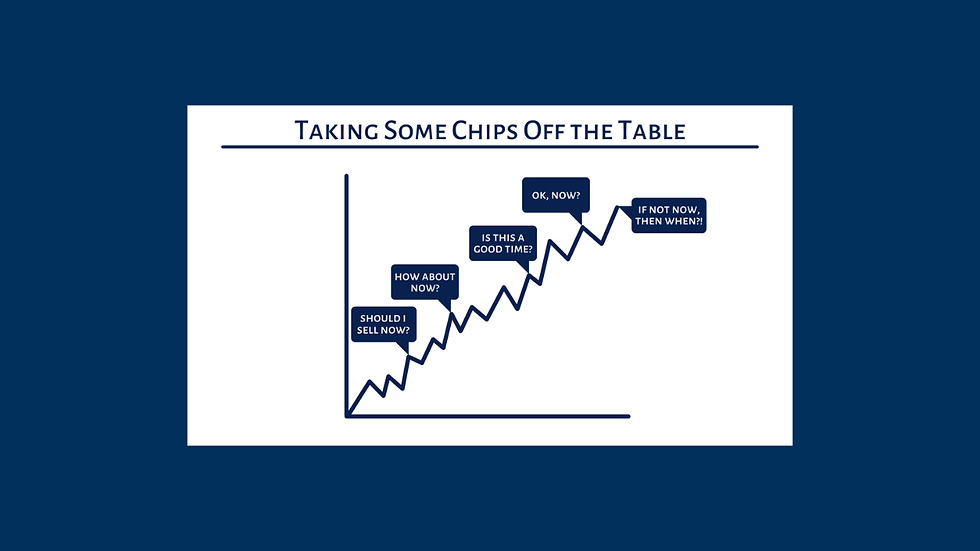

Should I take some “profit” off the table and de-risk the portfolio?

Let's be honest -- the 2020 rollercoaster is not something that people want to go through year after year. This question pops up just about every year and normally the answer is: "if you move to cash, the probability of success in your plan actually decreases long-term."

This year the answer might be a little different. Generally, when taking on a new client, they will fill out a risk profile questionnaire. It has questions like, "when the market went down in the late 2000's, did you: hold, buy more, or sell your investments?" Basically, that question is a behavioral question that is supposed to help the advisor understand what you would do as an investor when the next downturn happens. The problem is, your mindset when answering that question is totally different than when you're actually in the middle of a market downturn.

I think it's time for most people to revisit their real risk and volatility profile. If 2020 made you lose sleep, maybe it actually is time to take a less aggressive approach. There are pros and cons to doing this, however. If you wish to experience less volatility (and therefore, the possibility of lower returns), you will probably have to save a higher percentage of your income (or spend less for those already in retirement) to make up for the shortfall. With every decision, there is an opportunity cost (just like Economics 101 you learned in high school).

Best funds for 2021? Should we buy the bad performers from 2020? How can we pick the winner for 2021?

This one is a classic. Every year I have people tell me that "if I would've just held *insert ticker symbol* it would've beat the market.

Toward the end of 2020, something interesting was happening in the S&P 500. The companies that really propelled the comeback from late March through the end of the year weren't performing as well as they had been. In fact, there were a few days that the massive company names (Amazon, Google, Apple, etc.) were down, yet the index was still up. That's the beauty of holding a basket of stocks. If some are down, others are likely to be up. Therefore, lessening the amount of risk/volatility in your portfolio.

It's also a case showing how hard it is to beat the market consistently. Ben Carlson writes a great piece here, titled, "A Short History of Chasing the Best Performing Funds."

For most of my clients, we aren't necessarily aiming for the single home run of the year. It's a mindset thing. The risk of underperformance year after year if we wrong outweighs the potential that we could *maybe* get one right.

Isn’t it time for the market to correct or have a downturn?

Not all downturns are 35% like in 2020. However, every single year (on average) there is a downturn of 5%, and every 3 in 5 years a downturn of 10%. Even if there is no legitimate reason. Remember, the market is forward-looking, so the catalyst for a downturn that you may be thinking of could already be priced in.

The truth is, and will always remain that, "we don't know." If we cannot control it, what is the sense in worrying about it?

Instead, let's focus on what we can control. Savings rates, withdrawal rates, fees, tax management, etc. I promise that you'll sleep better at night than worrying about whether the market will be up or down tomorrow.